Isabelle Pauwels—Triple Bill

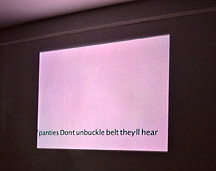

Still from Triple Bill, 2007

Still from Triple Bill, 2007

Isabelle Pauwels

Triple Bill is in some sense a documentary, but it will disappoint in many ways if

it is only seen as attempting to convey a clear picture of its subject. In fact, its

subject is never pictured, if one can claim something so simple as “a subject” for this

work. Pauwels visits porn theaters in Vancouver and records a few of these visits, but

not in a conventional way. She does this in ways that short circuit the psychic economy

of porn. No pornographic images appear in the work, and little clearly discernable audio

from the movies she attends is heard in Pauwels' work. What we are left with is largely a

textual representation of the visits.

Text precludes certain elements that are important to what we typically think of as

pornography. Figurative representation, the missing element here, allows one a certain

hold on the subject—this is reflected strongly on the metaphors we use; we capture images,

shoot video, take pictures, etc. The textual account of events is subjective in a way we

conventionally consider opposite to the image's apparent objectivity. Pauwels plays with

these conventions, withholding the image, and, one might say, feminizing the pornographic.

But this does not, and is not intended to, eliminate or subsume desire and pleasure, or

even the narrative, for that matter. There is still tension in the narrative and the

work offers arousal, even if not in an entirely straightforward sense.

The sense of the subject eluding one's grasp is heightened by the speed at which the

text scrolls. It is nearly impossible to catch all of the words on the screen, especially

when, as sometimes happens, more than one dialog is occurring simultaneously. This

intensifies the awareness of working to get the story and foregrounds its subjectivity

and point of view. Gone is the seemingly transparent window of the documentary film or

photograph, which seems to have returned with such a vengeance in recent years. The

recent return of this trend often presents a self-conscious subject, but ignores the

subjectivity of the viewer, instead packaging the work in the most easily digestible form possible.

Still from Triple Bill, 2007

Still from Triple Bill, 2007

Isabelle Pauwels

Pauwels' work forces one to be a conscious participant in the construction of the story

and acknowledges inter-subjectivity—subjectivity cannot exist in isolation. The subject

is necessarily active and engages with the work, or the work's own subjectivity, if you

will. Pauwels is not entertaining the viewer, not simply producing something to be

consumed. This also separates Triple Bill from its presumed subject matter. Though,

when one thinks about it, pornography is an unusual mix of entertainment, consumption

and engagement. Viewers demand a certain amount of explicitness, but are required to

use their imagination, if for no other reason, because the scene is not present to them.

They must imagine themselves within the scene offered to them.

Triple Bill requires much more than this, as stated above. There is a history of

avant-garde film that Triple Bill is engaging here. The film evokes Guy Debord's infamous

1952 film, Hurlements en faveur de Sade (Howls for de Sade, or literally, Howls in favor

of de Sade).[1] Debord’s film implies pornography

by including the name de Sade[2] in its title,

but the film is the furthest thing imaginable from the conventional notions of pornography.

The film, eighty minutes long, alternates between a completely white screen with voices

quoting various fragments of text, and a black screen and a silent soundtrack. The final

twenty-four minutes of the film are dark and silent. The howls came from the audience.

Though Pauwels goes nowhere near such extremes, and seems to have no intention of

deliberately disappointing her audience, her work does perform an act of resistance.

But this resistance is complicated in that it examines narrative structures and documentary

forms while constructing a documentary narrative. In some sense this is classic modernist

self-criticality, the kind of interrogation of an artistic medium that led painters to

paint monochromes when they asked, “what is painting?” or, “how much can I get rid of and

still call it a painting?”

However, Pauwels has incorporated critical historical lessons into her work. She is

no longer interrogating a medium, but a practice, a way of making art and the position

of that maker. She rebuffs the possibility of objectivity and the documentary in its

oft-practiced form by breaking the cardinal rule of journalism—she doesn't just spin

the story, as a woman in a male space, she is the story. She creates the entire situation

with her presence. She is an intruder into this space and the object of desire, but

in a way that doesn't make sense within the conventions of the pornographic theater.

Women in this space, whether on screen or in the audience, are understood to be there

for ulterior motives; to be blunt, they are seen as some sort of prostitute. From the

point of view of the male moviegoers, the actresses are paid for their roles and the

women in the theater are thought to be there to perform sexual favors for money or drugs.

Pauwels' presence creates a major schism in that reality. She is there of her own accord

to satisfy her own impulses, not at the service of the male clientele.

What has struck me most about Pauwels' work is this forthrightness. Pauwels' work is

admirable and brave, adjectives rarely used to describe art. She takes personal risks

that matter. This is all the more striking in an era of art making that promotes raucousness,

but risks little. Her work deals with important aspects of contemporary life. Life is

in some sense a subject of experimentation, and this experimentation in turn improves life.

— Aaron Van Dyke